Folding for Data Availability: Fun for All Sizes

Data availability proofs are pivotal in distributed systems, particularly in blockchains, where they authenticate data blobs and prove data storage. While Filecoin, Ethereum light clients, and rollups all rely on these proofs, current solutions often fall short.

Existing solutions often employ variants of Merkle trees or variants, such as Verkle trees. Much work has been done to improve the practicallity of data-availability solutions at scale. Still, current solutions for large files often suffer from one of the following issues:

- The proofs are large

- To make the proofs smaller, expensive and slow techniques are employed (I.e. using a SNARK to prove the tree path)

- To make the compression techniques less expensive, newer, algebriac hash function are used. These hash function have not stood the test of time (i.e. the Poisiden hash function)

So, can we get around these issues? Would it be possible to use a compression technique without using an algebriac hash function? The answer seems to be yes!

In this post, we will explore a new technique for generating data availability proofs, primarily leveraging cryptographic folding and the Blake3 hash function.

A Brief Introduction

At a high level, the Blake3 hash function has an in-built Merkle-tree like mechanism to produce a hash of a large amount of data. So, to produce a data-availability proof, we simply need to generate a proof of knowledge from a random leaf to the root. For anyone familiar with Merkle trees, producing a proof requires verifying hashes where is the number of leaves in the tree. Even though the scaling is relatively efficient, there is still a significant overhead in terms of number of constraints in real-world proving systems.

However, the folding technique can allows us to quickly generate proofs in parallel for individual hash verifications in the tree and then combine them to produce the final proof. Unfortunately, at the time of writing this post, the parallelism in the folding technique is not yet implemented in the proof systems. Nontheless, folding allows for simpler circuits for proving.

Data Availability Proofs at a Glance

Data availability proofs are a crucial component of distributed systems. They are used to ensure that data is available to all participants in the system. In the context of blockchains, data availability proofs are used to ensure that all participants have access to the data that is being stored on the blockchain.

Though there are multiple ways to instantiate data availablity proofs, we will focus in on Merkle-tree based approaches. In a Merkle tree, data is stored in the leaves of the tree each inner node’s value is the hash of its children. By the magic of collision resistance and cryptography, we can expect that any party which can provide a valid path from a leaf to the root of the tree must be providing the originally hashed data. In other words, it is (cryptographically) impossible to cheat and come up with a path which yields the same root hash but is not the original data.

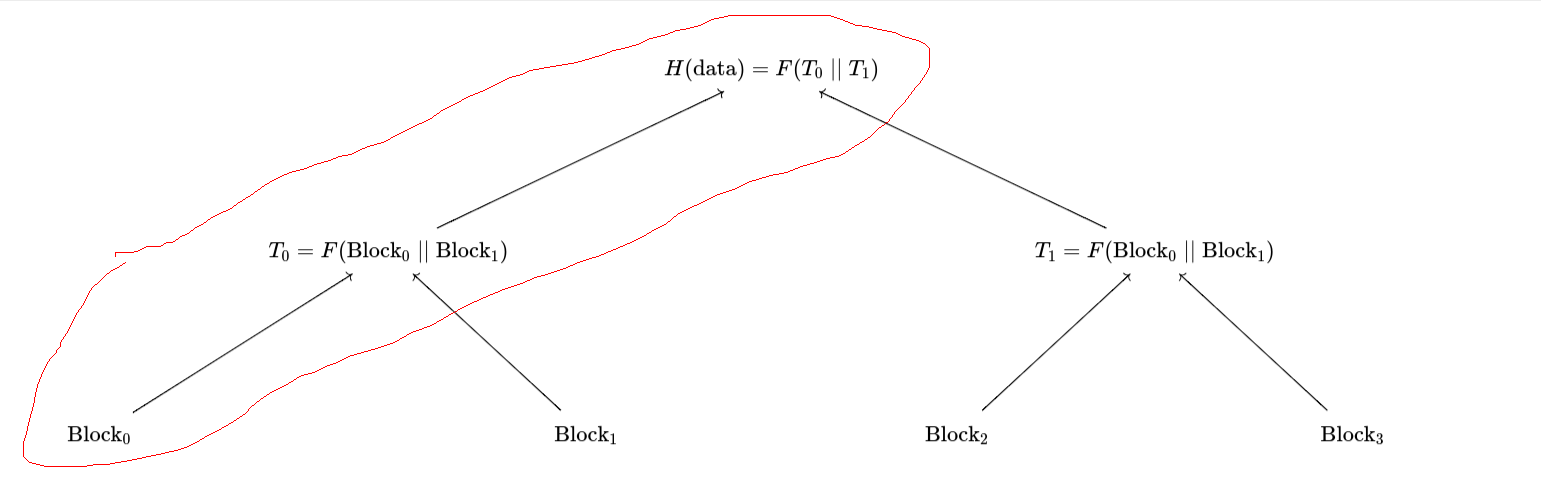

A picture of a Merkle tree where H is the hash function. For a data availability proof with 4 blocks of data, the data is stored in the leaves.

As always, Wikipedia is a great resource for learning more about Merkle trees.

But what now? We do not get a data-availability scheme by simply having a Merkle tree. Indeed, imagine that for Bob to prove to Alice that he has the data, he must provide any path from the leaf to the root. Bob can then simply store the path from one leaf to the root and throw out the remaining data. Bob can then provide the path to Alice and Alice will be none the wiser.

Instead, we need Alice to leverage randomness. Now, Alice can ask Bob to provide a path from a random leaf to the root. Bob cannot simply store the path from one leaf to the root and throw out the remaining data. If he does this, he will be caught out when Alice asks for a path from a different leaf to the root. Bob must store all the paths from all the leaves to the root.

Folding at a Glance

For simplicity, we will think about SNARKS without the ZK part (i.e. they do not preserve secrecy). In general, a SNARK can be thought of as consisting of a witness (which we will refer to as ), a public input, , a public output, , and a circuit . Though often not framed in these terms, we can think of a SNARK as a proof that the circuit with inputs returns back the public output .

For our purposes, we can think of folding as doing a sort of iteration over a circuit. We will iterate the circuit for a number of rounds, , and at each round, we update some running proof state. For round , the update will prove that given the output from the last run, and witness , then . Moreover, this proof will be “combined” with the proof from the previous round to produce a new proof for the current round.

In other words, we have that after round , the current proof proves that . The magic of folding is that each round’s proof can be produced in parallel and then combined to produce the final proof. (TODO: source)

A diagram of the folding process. The circuit, C, is run sequentially for each round and the proofs are combined to produce the final proof.

Blake3

The Blake3 hash function is surprisingly suited for folding. Not only does it use a Merkle-tree like structure to hash large amounts of data, but the inner-workings of the hash function can be broken up for folding in a natural way.

The Blake3 hash function’s design is a variation on the Blake2 hash function. It is designed to be fast and secure and is based off of one core building block: the compression function.

A Note on Definitions for the Compression Function

Technically, the compression function in Blake3 is not the thing that I am calling a compression function here. The function that I am referring to simply runs the compression function multiple times (8 in the case of Blake3). The number of rounds is a parameter of the hash function and can be adjusted to trade off between speed and security. See the Wikipedia page on block ciphers for more information.

The compression function can be thought of as a function which takes in a -bit state, a bit key, and some metadata. The function then produces a -bit, hard to invert state. The hash function itself is built up by chaining together multiple compression functions in various ways.

First, the data is split up into blocks of bytes (or bits). Each block is then processed sequentially by splitting the block into -bit chunks and then feeding them into the compression function. The first chunk uses a fixed bit key. Then, for all other chunks, the bit key is set to the prior chunk’s output. The last chunk’s output is the hash of the entire block.

All the blocks are then hashed together in a tree-like structure to produce the final hash. The “hash function” here is the compression function. We then get a hash algorithm which looks something like the following diagram:

Putting it All Together

Now we are cooking 🍳! We have review all the building blocks of how to do data-availability with folding. The idea is that our circuit is going to be the “compression function” of Blake3 as well as some extra logic to handle whether we are chaining together compression functions (as when hashing 1 block) or hashing multiple blocks together into a tree.

The initial public input is going to be the index of the block for which we want to prove membership. Assuming that the data block takes up the full bytes, we will have approximately rounds of folding where . For the first 16 rounds, the prover shows knowledge of the block. I.e. the proof verifies that where is the hash function and is the hash of the block. For the remaining rounds, the prover shows knowledge of a Merkle path from the block to the root of the tree.

The First Rounds

Notice anything similiar about the two diagrams bellow? (The first is the diagram we used to explain folding and the second for the Blake3 hash function for one block)

Exactly! Folding fits almost perfectly with the structure of the Blake3 hash function where message chunks are the witnesses .

For each round, , the prover uses witness where is the -th chunk of the block. The public input is the index of the block, a 256-bit string as well as a few flags to keep track of where we are in the hashing. The output is the hash of chunks through . The output of each round is fed into the next round as the 26-bit string and used as a bit key.

Extra complication with circuit

As an aside, this usage requires a little bit of extra logic within the circuit to handle the fact that the bit key is actually fixed when using the compression function for tree hashing.

The Remaining Rounds

The remaining rounds are used to prove knowledge of a Merkle path from the block’s hash to the root of the tree. The circuit and input are similar to the first 16 rounds, but the flags are different. Now, the witness is the sibling hash to each node in the path. The 256-bit string input is now used as input to the compression function rather than as a bit key. The output of the circuit is the hash of the block and the sibling hashes.

Diagramatically, this can be thought of as folding over one path in the Blake3 hash function’s tree. For example, if we are trying to prove knowledge of the 1st block in a tree with 4 blocks, the folding be down over the circled path in the following diagram:

The Final Proof

So, now we are left with a proof that the prover knows the block and a Merkle path from the block to the root of the tree. The proof is produced by running the circuit for each round in parallel and then combining the proofs to produce the final proof. Nice!

Conclusion

Though we still need parrallization support for folding, we are well on our way to data-availablity proofs which are both fast to generate and small in size. With some work, authenticated data structures will become easier and easier to employ in real world systems as overheads decrease. To keep up with progess check out the Hot Proofs Blake3 library.